Right after lunch I see one of my favorite people. Rabbi Jonah bar Simon is headed for my marketplace stall.

“Rabbi!” I smile, throwing my arms wide.

He doesn’t make eye contact. He just slams a heavy jingling bag on the counter.

Hadad, a baker, has the stall next to mine. When Haddi recognizes my visitor, he gives me a wink and a smirk.

“Your mother must be so proud,” sneers Rabbi Jonah. “Her little boy, the tax collector.”

“Well, she wanted me to be a rabbi,” I say. “But I decided to make an honest living.”

If looks could kill, Rabbi Jonah would be murdering me right now.

“Haddi, it’s all here!” I marvel, counting my loot. “The Rabbi paid up this time! What do you think happened?”

“Did you send Gaius to have a little talk with him?” Haddi asks.

Gaius is a centurion in the Jerusalem garrison who supplements his paycheck doing side work for me. After they meet his sword, an amazing number of deadbeat taxpayers cough up.

“If we’re done here, I want a receipt,” the rabbi says, slapping a sheet of parchment on the counter.

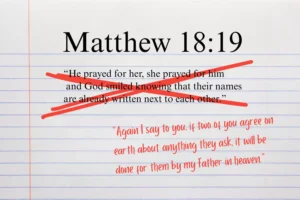

I scrawl “tetelestai” across his tax bill.

“What does that say?” he asks suspiciously.

He can’t read my handwriting, which is atrocious. But I decide to have a little fun.

“Haddi, this is tragic,” I lament. “The Rabbi’s spent too much time in the Hebrew Scriptures. He’s forgotten how to read Greek.”

“I understand Greek!” insists Rabbi Jonah.

“Sure you do,” I say doubtfully. “Haddi, tell the man what I wrote on his bill.”

“It says ‘tetelestai,’” Haddi explains slowly, as to a child. “It means ‘your debt is paid in full.’”

“I know what ‘tetelestai’ means!” the rabbi seethes. “THANK THE LORD I’M NOT A TAX COLLECTOR!”

He snatches his parchment from the counter. “Or a BAKER!”

Haddi and I share a good laugh as the rabbi stalks away into the crowd.

This is why Jonah bar Simon is one of my favorite people. He’s rich, which means a big tax bill. He’s a coward, which means Gaius can make him pay. And best of all, he’s good for a laugh. Haddi and I enjoy the rabbi’s parting shot all afternoon: “Thank the Lord I’m not a tax collector . . . or a baker!”

But around four in the afternoon, after Haddi sells out of bread and closes his stall, I’m left alone with my thoughts, which immediately turn to my family. And that’s dangerous, because Mom (may she rest in peace) did hope I’d become a rabbi. And I do worry God will punish me for being a tax collector. Besides, whenever I think about family, I remember Bennie . . .

When Bennie comes to mind, it’s time to go home. Dinner and wine will help me forget about my kid brother.

I hope.

* * *

As I’m about to close my stall, a man I’ve never seen before walks through the marketplace. He dresses way too nice to be from this backwards hick town, and I wonder what he’s doing in Jerusalem.

He spots me and makes a beeline for my stall.

“Are you Joseph?” he asks eagerly. “Joseph bar Judah?”

“Who wants to know?”

“Luke, from Decapolis,” he says, reaching out to shake my hand. “Not originally, but that’s where . . . I’m a physician. Of course, that isn’t why . . . are you? Joseph bar Judah?”

I nod, a little confused. This guy may know medicine, but he needs some lessons in conversation.

“I’ve been looking for . . . people told me you saw . . . what do you know about crucifixion?”

I don’t consciously decide to do it. But suddenly I’m lunging across the counter of my stall, reaching for Luke’s neck.

“Take it back!” I shout. “Take it back before I knock your teeth down your throat!”

Luckily, Luke has good reflexes and jumps backwards. “Whoa . . . sorry, buddy, I didn’t mean . . . I’m writing a book! About Jesus.”

I look around. The moneylender across the lane is staring, and I see a mother a few stalls down pull her daughters closer.

Trying to recover some dignity, I stand up and brush off my robes. “Jesus . . . right. Sorry. I thought . . .” My temper flares again: “You can’t just ask people that! Not out of nowhere. Crucifixion’s a sensitive subject.”

“Sorry, I didn’t know—”

“Well, it had to happen eventually,” I sigh. “I was bound to meet one of you nut-jobs who worships a dead guy.”

“Jesus isn’t dead!” says Luke earnestly. “I’ve been interviewing eyewitnesses—”

“And I’m Emperor Tiberius. When the ‘risen Messiah’ walks into my living room—”

“But he appeared to 500 people—”

This guy really seems to believe what he’s selling. Just like I believed, back when . . . eh, never mind.

I pick up my money bag to go home. “Whatever you say, buddy. I got dinner waiting.”

“Were you in Jerusalem last Passover?” Luke asks.

“Where else would I go?”

“Then maybe you saw . . . like I said, people told me . . . the crucifixion!”

I lean across the counter and point a finger in his face. “I. Don’t. Wanna. Discuss. It. You mention crosses one more time, and I’ll introduce you to my buddy Gaius. He’s a centurion. Maybe he’ll let you try crucifixion firsthand.”

“I’m sorry I offended you,” says Luke. Then quietly: “It was someone from your family, wasn’t it?”

I’m confused again. “Someone from . . . what?”

“The person who died. On a cross.”

I freeze. How does he know?

“I heard about your younger brother.”

Nobody in Jerusalem knows about that. Not Haddi, not the servants, nobody except . . . this guy went to my house! Rachael and my eldest son are the only ones I’ve told.

“Who do you think you are, talkin’ to my family?” I’m about ready to jump over the counter again.

“I’m so sorry,” says Luke softly. “No one should die like your brother did.”

This guy’s sympathy, or whatever it is, is really irritating. It would be easier if he was trying to use it against me.

Then it hits me: the game he must be playing. If it gets out that Bennie was a traitor—say, if Luke told Gaius—my whole family could be in danger. Where the Romans are concerned, if your kid brother is rotten, you might be rotten, too. He’s trying to extort me!

“How much?” I ask nervously. “How much to stay quiet about Bennie? I can do fifty aurei now, and if you come back on Friday—”

Luke shakes his head with a gentle smile. “I don’t want your money.”

This must be part of his scam—denying he’s in it for the cash. “Come on, a nice Jesus Freak like you wouldn’t turn me in, right? Even if I am a tax collector . . . right? What are you after?”

“Just your story. How it connects to Jesus. But if you don’t want to tell me . . .” He shrugs to say it isn’t that important. “I should go.”

Luke turns to walk away.

Is this guy for real? Maybe he honestly just wants my story. But if he runs to Gaius . . . he could put my whole family’s heads on the block. I have to keep him here while I figure out what he’s up to.

“Buddy, you don’t have to go . . . you want my story? Sounds like you know most of it already.”

Luke looks at me attentively; he clearly wants to hear my tale. But I notice that he keeps a bit of distance between us. I can’t blame him: this way I can’t come over the counter again.

I haven’t thought much about Bennie in ten years . . . except at the last Passover, of course. But I guess it’s time. If I make Luke-the-Physician happy, maybe he won’t rat me out, and maybe my family’ll be safe for another day.

Maybe.

* * *

“We were a good Jewish family. Kept kosher. Said the prayers; followed the Law. And it wasn’t for show. We believed,” I tell Luke.

“I know, I know . . . a tax collector who loves God? But I did—our whole family did. When Dad prayed, he was sure there was Somebody listening. Me and Benjamin were his only sons, and we were growin’ up to be pillars of the synagogue. ‘Cause we believed, too.

“But Bennie . . . he was one of those kids. The ones who wanna be liked a little too much? Who do whatever their friends do? That was my brother. And his friends . . . well. Dad warned him. I warned him. Rabbi Jonathan warned him. But it’s like Bennie couldn’t hear anybody but his new pals.

“When he was in his early twenties, he fell in with a gang of Zealots. Naturally, they did what Zealots do: rebelled against the ‘Roman oppressors.’

“‘Living in an occupied country isn’t so bad, Bennie,’ I would tell him. ‘Keep your head down and your nose clean; you’ll be fine.’ But Bennie wouldn’t have it. Independence was ‘God’s Will for His Chosen People.’”

I pause for a deep breath. Luke doesn’t interrupt me, doesn’t say a word. He just nods in the right places.

“So Bennie and his pals planned their big insurrection. Kill the little Roman garrison stationed outside town! Take control of the village! Once the nation realized what God was doing, all Israel would rally to The Cause. There would be a REVOLUTION!

“Except the revolution never happened, because most of us knew better. Oh, Bennie’s pals managed to knock off the soldiers—there were only a dozen or so. The Zealots got to strut around town like kings for a week.

“But then reinforcements from Jerusalem arrived, and the Romans didn’t just kill the Zealots who started it. Oh, no—they punished the whole town. Two of my sisters got run through with swords. Mom was already sick, but the broken heart did her in. And Benjamin . . .”

I brush a hand across my eyes. I can’t get through this part without crying . . . even if my brother doesn’t deserve tears.

“Bennie didn’t die in the battle,” I say. “Nah, that would’ve been too easy. The Romans made an example out of him and five of his closest friends.

“Three days. It took three days of agony, nailed to a cross outside town, for him to give up the ghost. Me and Dad . . . the whole time he’s hanging there, we’re praying for Bennie. Praying for him to die quicker.

“Somehow, Dad stayed faithful. I’m sure he still prays every morning and worships every Sabbath. Me? I haven’t been to synagogue since . . . well, since Bennie. But I couldn’t go if I wanted to. The rabbi threw me out when he heard I was a tax collector.

“I got kids, okay? Suppose the Romans come after me. How would Rachael feed six mouths without a husband? That’s why I took this gig: ‘I can’t be a traitor like my kid brother, Mr. Centurion. I’m a collaborator!’

“Everybody knows that tax collectors . . . we set our own rates, y’know? So long as Tiberius gets his, he doesn’t care if I charge extra. That means feeding my babies is never a problem. Say I meet a deadbeat taxpayer: I decide when to say ‘tetelestai.’ Till I announce his debt’s paid in full, he owes me. And if he doesn’t like it, he can take it up with Gaius.

“Last I heard, Bennie’s widow was begging—literally begging—for food. I’d help if I could, but she’s too fancy to take money from a tax collector. Fine: I hope her pride keeps her warm at night. Me, I’m laughin’ all the way to the bank. If you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em!”

Luke hasn’t said a word as I’ve been spilling my guts. But now he gives me a reproachful look—the same look I get from Rachael when she catches me in a fib.

“Okay . . . maybe I don’t laugh much,” I say reluctantly. “I wish . . . it’d be nice to go home. See my nieces and nephews; find out if Dad’s alive or dead. But if I showed up in the old hometown, I’d get stoned to death.”

This is why I don’t talk about Bennie. I loved my baby brother, and when I start talking . . . well, it’s easier to try and forget. Now that I’m letting it out, the words just won’t stop.

“I hadn’t thought much about my little brother in years. Even the nightmares had stopped, mostly. But then came last year’s Passover, and the thing with Jesus . . . everything came back to me. Especially the guilt.

“I always steer clear of Skull Hill. That’s the Romans’ favorite place for crucifixions, and I never wanna see another one. Anybody nailed to a cross looks about the same. I mean . . . well, they all look like Bennie to me.

“Unfortunately, staying away didn’t work this Passover. I was chasin’ down a delinquent taxpayer. Guy owed me two hundred aurei, and I heard he was near Skull Hill. So I wound up on the scene just in time to see your pal Jesus kick it.

“I listened to Jesus preach once. About peace and forgiveness and . . . other useless stuff. But I didn’t know it was him on the cross till I overheard the soldiers.

“‘This joker said he’s the Son of God,’ a soldier scoffed. Another replied, ‘Guess that means his daddy doesn’t love him very much.’ The whole group thought that was hilarious.

“Y’know how something can be so terrible you can’t look away? Even though you don’t want to see it? Watching Jesus die was like that. There was a fisherman standing nearby, and a couple older ladies sobbing—I think one was his mom. I could tell Jesus was almost gone because he was barely breathing.

“Then all of a sudden, Jesus seemed to get this burst of energy. He reared up on the nails in his feet, took one last mighty breath, and shouted something I couldn’t make out. When he sagged back down . . . he was gone.

“I know he must’ve been special. Just as he died, the sky got dark. There was an earthquake. I saw this rock—more like a boulder—split in half. There were rumors . . . I don’t believe it, but people said . . . dead bodies walked right out of tombs. Crazy, right?”

There’s a long pause. I don’t say anything: I stare into the distance. Luke doesn’t say anything: He stares at me.

“I wish I could’ve . . . talked to him. Jesus. Just once. Somebody told me he forgave the soldiers who were killing him. Maybe he could’ve . . .

“When we were little, me and Bennie used to play what we called The Rescue Game. It always started the same: An evil villain kidnapped our sisters. Mom and Dad were helpless, so it was up to us brothers to defeat the villain and save the girls. We thought it was the best game ever.

“I believe. Even now, after everything . . . I believe there’s a God in heaven. It’s not God’s fault Bennie joined up with knuckleheads. Not his fault I’m a professional coward who collects taxes to save my skin. Maybe this Jesus was God’s son. Maybe he even came back to life like you said. How would I know?

“But here’s the thing. Me and Bennie already knew when we were little that if somebody’s in trouble, you rescue them. Bennie, however screwed up his ideas were, tried to do that. Me? I turned into a professional villain. I don’t rescue people. I take ‘em for every quadrans they have.

“I’d pray, except I know God doesn’t hear sinners. I’d go to synagogue, except Roman collaborators aren’t welcome. I’d beg God, plead on my knees, except . . . eh, forget it. It’s like I owe him fifty years of back taxes and I’ll never pay it off. But if I could do it over again . . . well, I’d try to stay right with him. Before I got past rescuing.”

Luke nods slowly. There’s a long silence between us. I may have just spilled my guts all over the place. But on the bright side, it’s pretty clear this guy isn’t going to turn me in to Gaius.

“Sorry you had to listen to my sob story for a few lines about Jesus,” I finally say, standing to leave. “I better get home before Rachael sends a search party.”

“You’re not past rescuing,” Luke says quietly.

I roll my eyes and laugh bitterly. “I wish.”

“I mean it. Jesus showed us nobody is beyond—”

“Don’t preach me a sermon.”

“But I can prove it, because Jesus said—”

“You got the story you came for; don’t try and convert me.”

“But Jesus—”

“Can’t I just head home and eat? Go back to Decapolis, will ya?” I yell at him.

My patience is shot. I’ve just relived the worst moments of my life, and I feel like I could curl up in a ball and cry for days. To be perfectly honest, I also want to stop thinking about God, because the only thing he does for a slimeball like me is make me feel guilty. Guilty for collecting taxes for the Romans. Guilty for cheating my countrymen to make a buck. Guilty for not figuring out some way to play The Rescue Game one more time and keep my little brother from being tortured to death.

I finally end the conversation by walking away.

But Luke won’t quit. He calls after me: “You want proof that God takes away guilt? Pays off those back taxes you owe?”

I don’t stop. Luke’s yelling now as I get further away.

“You remember that last shout from the cross, the one you couldn’t quite hear? You know what Jesus said? The word was ‘tetelestai!’”

I freeze. I turn around and see Luke staring at me. A look like a long conversation passes between us.

I start walking—no, running—back towards Luke. I’m not sure what to think about this Jesus guy. But I want to find out why he said my debt was paid in full.

Copyright 2019 George Halitzka. All rights reserved.