Marine veteran J.J. Hanson and his wife, Kristen, were new parents when they learned that J.J. had a rare form of stage 4 brain cancer. Doctors gave him four months to live.

Around the same time, newlywed Brittany Maynard was making headlines as she faced the same form of cancer. Her home state of California did not allow assisted suicide, so Maynard and her husband moved to Oregon, where they found a doctor who could and would prescribe drugs to end her life.

Brittany died on November 1, 2014. Less than a year later, California passed the End of Life Option Act.

“J.J. later admitted that during his illness, he sometimes felt such despair that he may have taken a lethal prescription had it been legal in New York, where we lived, and if he had it in his nightstand during his darkest days,” Kristen wrote. “There’s no telling what would have happened to J.J. and our family if lethal pills were available to him during that dark period.”

What are assisted suicide and euthanasia?

As a person nears the end of his or her life, whether due to illness or old age, there are many decisions to be made. Patients are free to choose their treatment or to refuse treatment, but in some places in this country and around the world, patients are legally allowed to request a third option: a lethal drug dose.

The difference between assisted suicide and euthanasia lies in who administers the life-ending dose. Assisted suicide means the patient takes it himself, while euthanasia occurs when a doctor administers it — often at the patient’s request, or in some cases, the patient’s guardian; this includes parents. Both are different from electing to cease ongoing treatment for a disease or condition.

“Removing treatment from a person who is in the process of dying is completely different,” says Lois Anderson, executive director of Oregon Right to Life. “Sometimes people get these confused and there are important ethical questions in end-of-life care. However, the intent of assisted suicide and euthanasia is always to end the life of a suffering person. Increasing a dose of pain medication or removal of a breathing machine may result in death, however the intent is to bring comfort.”

Assisted suicide and/or euthanasia is currently legal to some extent in Belgium, The Netherlands, Switzerland, Canada, Colombia, Luxembourg, and parts of Australia and the United States. Oregon was the first U.S. state to legalize assisted suicide in 1997, with seven other states and the District of Columbia later following suit.

At first glance, assisted suicide can seem like a compassionate last-resort option for a suffering person. If someone wants to die, why shouldn’t we let them?

The case for life

Supporters of assisted suicide claim that people who experience extreme suffering or a grim prognosis should have the right to end their life in their own time and on their own terms. In this view, the elderly, disabled, and seriously ill should be legally allowed to commit suicide. But as much as our self-serving, independent natures want it to be, is that really our decision to make?

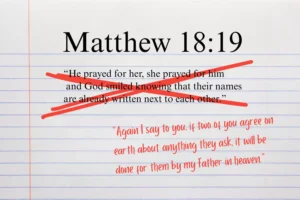

Human beings are created in the image of God. God is both the author of life and the arbiter of it. Taking life — whether ours or others’ — is wrong. It’s taking on a responsibility that is God’s alone. This is true whether we’re talking about abortion, suicide, assisted suicide or euthanasia.

After Joni Eareckson Tada’s diving accident left her a quadriplegic, she often wanted to end her life. In her book “When Is It Right to Die?” Joni says she begged friends to sneak in sleeping pills or razors, and when she was alone in her room, she frantically thrashed her head around, hoping to further damage her neck.

But nearly 50 years later, Joni wrote an open letter to Brittany Maynard. “If I could spend a few moments with Brittany before she swallows that prescription she has already filled, I would tell her how I have felt the love of Jesus strengthen and comfort me through my own cancer, chronic pain and quadriplegia.”

We can’t gloss over Joni’s — and others’ — very real and intense pain and suffering. But as Anderson explains, “It is not humane to eliminate the sufferer rather than the suffering.” “Underneath the language of compassion and care is the intent and design to end a human life.”

Far-reaching effects

A quick look at the facts shows that for Oregon, assisted suicide has not been a problem-free choice.

One study found several concerns:

- Even though laws state that the patient must have a prognosis of less than six months to live, in some cases the patient was listed as having no illness whatsoever

- While suicidal tendencies often point to underlying mental or emotional needs, 96 percent of patients referred for assisted suicide in Oregon never received a psychological evaluation

- Ironically, a painless death cannot be guaranteed. “At least 30 patients in Oregon (three in 2016) have regurgitated some or all of the drugs. In all, six regained consciousness after taking them and died later. Five died from their underlying illness, and one patient in 2012 apparently died six days later from the effects of the drugs. No patient who has gone through this experience once seems ever to have tried again.”

There is also concern that when certain people are allowed to kill themselves, we are effectively telling others in similar situations that we don’t believe their lives have value. Unfortunately, Oregon’s elderly population proves we are communicating that all too clearly. Oregon Right to Life points out that their state “has an elderly suicide rate that is 156 percent of the national average.”

Even if all technical regulations were closely followed, John Stonestreet explains that legal limits are often temporary:

“Physician-assisted suicide is sold to the public as a ’compassionate’ measure, necessary to spare those with no reasonable chance of recovery the unbearable pain and suffering of the last days of their lives. In every context in which it has been made legal, however, what might be called euthanasia-by-another-name has never remained limited to the rare instances on which it was sold. Once it is decided that certain lives are not worth living, the list of people eligible for physician-assisted suicide inevitably grows. As the list of people without intrinsic value grows, it becomes impossible not to re-evaluate lives based on some other criteria, perhaps convenience or financial costs. It’s a small step indeed from ‘eligible to die’ to ‘expected to die.’”

In California, one woman’s insurance refused to pay for her medical treatment, but offered an alternative: For $1.20, she could opt for assisted suicide instead. In The Netherlands, some citizens expressed fear of going to the doctor because their doctor might push for euthanasia, and the law has expanded to allow children to request euthanasia. Parents who have a child who is a year old or younger can also request euthanasia in what’s known as the Groningen Protocol. Belgium also allows the euthanasia of children if the child, parents and medical professionals all approve. The child must have a terminal diagnosis, incurable disease, be near death or in chronic pain.

Determining which people qualify for death is a very slippery slope. What if an elderly person is heavily influenced toward assisted suicide by their children? What if a nonverbal disabled person has communicated no such desire to die, but their legal spokesperson insists they would want to? What if a dementia patient once wrote down that she wanted assisted suicide, but changes her mind when the time comes — and her doctor and children physically hold her down to administer the fatal dose?

Each of these scenarios has happened in the last 15 years.

Sharing hope

A few weeks ago, I came across a photo on social media of a man standing on the outside of a bridge’s protective railing. He had considered jumping to his death, but several passersby grabbed him and gripped him close. They secured him with a rope while someone locked their arms around his neck, and another reached through the railing to grip him around the knees.

Those impromptu rescuers dropped whatever they were doing to save a hurting stranger. They perfectly illustrate our calling as found in Proverbs: “Rescue those who are being taken away to death; hold back those who are stumbling to the slaughter.” These strangers were physically and literally stopping a desperate man from ending his life.

Dr. Kenneth Stevens tells of a woman who came to his office requesting a lethal dose due to an inoperable cancer diagnosis. After explaining that he didn’t believe in assisted suicide, Dr. Stevens suggested cancer treatment, encouraging her to try to live long enough to see her son graduate and get married.

Twenty years later, Jeanette Hall is still alive. “If my doctor had believed in assisted suicide, I would be dead,” she said.

J.J. Hanson died of his cancer in 2017, but Kristen is grateful they fought as long as they could. “Those treatments extended his life beyond the initial four-month prognosis to three and a half years,” she later wrote. “If we had relied on the initial prognosis, given in to the depression and given up on hope, we would have missed out on so very much. Our oldest son, James, would never have gotten to know his father; our youngest son, Lucas, would never have been born.”

There are many heartbreaking situations that drive sufferers to a bridge or to a doctor who can prescribe a few pills. What if people knew they could count on Christians in their darkest moments? What if we extended true friendship to those who think death is their best hope? What if we reminded them of true hope and loved them like Christ loves us? What if we cared for them in their illness and decline, promising to walk with them each step of the way? What if we gripped them as tightly as those rescuers on the bridge, reminding them that death is not the answer?

“Oh, friends, we serve the God of all Hope (Romans 15:13),” Joni wrote to supporters of her organization, Joni and Friends. “Let’s roll up our sleeves and share Christ’s hope with despairing people we know; we dare not agree that a solution to their problems is physician-assisted suicide. Let’s come alongside people struggling against depression and help them discover that life is worth living.”

Copyright 2021 Lauren Dunn. All rights reserved.